The RIA system in Mexico: Using Compliance Cost to Apply the Proportionality Rule

Fabiola Perales-Fernández* | Jorge Velázquez-Roa** | July 2021

The views presented in this document do not represent official positions of Jacobs, Cordova & Associates.

This document has been adapted to be published as an Insights document. The original document can be downloaded at DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.15072858

Funding: The document was prepared on the authors’ own initiative and was not financed by public or private sources.

Abstract: Analysis of future impacts of regulatory proposals is a policy adopted by some countries to improve the quality of regulations prior to their enactment. To make this review efficient, countries have adopted the proportionality principle. The study presents the Mexican case of applying the proportionality rule under the concept of compliance costs, through a review of a random sample of regulatory impact analysis exemptions requested to CONAMER during 2010-2020. In the study we found that the maximum effectiveness of this approach was 71 percent in that period. We also found that the Mexican approach fails in two ways: the first, the application of the criteria of such concept, and the second, the (in)sufficiency of the concept of compliance costs to analyze all important impacts of regulation. We present some policy recommendations.

Keywords: Proportionality rules, Regulatory Impact Analysis, Mexico, Better Regulation, Conamer

* Regulatory Improvement Specialist www.mejoresgobiernos.com | https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1150-1655

** Director of Jacobs, Cordova & Associates for Mexico and Latin America www.regulatoryreform.com | www.linkedin.com/in/jorge-velazquez-roa-66715b

Introduction: The Rationality of the RIA’s Proportionality Principle: A Comparative Perspective

Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA) is a tool for making public policy decisions, particularly regulatory decisions. It allows evaluating the potential impacts of a regulation prior to its entry into force. Its objective is to better understand the effects of government action and ensure that it is effective and efficient.

The use of RIA as part of the public decision-making and regulatory formulation process has been gaining acceptance internationally and has spread rapidly over the last thirty years. In countries that have adopted RIA and have developed a formal and systematic system of ex ante review of regulations, coordinated by a regulatory oversight body —the regulatory review system— it is common for new regulatory projects to be supported by an RIA document to verify their appropriateness and, subsequently, to be formally adopted[1].

Naturally, not all regulatory projects have the same importance in terms of their impact and scope. For example, an energy or telecommunications reform project, which generally has a considerable impact on a country’s economy, requires a deeper level of analysis to measure and understand that impact, compared to a regulatory project that distributes or establishes functions within a Ministry.

The fundamental assumption that has prevailed in countries with regulatory review systems through the RIA is that the level of analysis should be proportional to the problem being addressed in order to allocate public resources for review and analysis. Given the budgetary restrictions faced by governments and the growing pressure to “do more with less”, countries have opted to focus their efforts and resources on preparing and reviewing RIAs in accordance with the principle of proportionality, which states that: the greater the potential impact or importance of the regulation, the greater the level and depth of analysis, more time for its evaluation and greater public resources allocated to its review; on the contrary, a regulatory project with a low potential impact will require a lower level of analysis, time and resources allocated to its evaluation and review[2].

Among the benefits derived from the use of a proportionality system that have been identified, the OECD (2020b) highlights the following:

- Ensuring that regulations with significant social impacts are adequately evaluated before they are approved.

- Ensuring that government resources are not unduly wasted in evaluating regulatory proposals with minor impacts.

- Avoid public consultation fatigue. Prioritizing broader consultation for those regulatory projects with significant impacts and where consultation can improve proposals.

- Improve the transparency of the regulatory review system, whenever there exist clear criteria that are easy to apply in practice.

A key point of the principle of proportionality is to determine which regulations require more complex and in-depth analysis before they are issued. To this end, it is necessary to establish proportionality mechanisms or rules to measure the potential impact or relevance of the regulation. At the international level, there are various rules for targeting or discriminating regulatory projects, which make it possible to decide the depth and extent of the analysis to be carried out according to the preliminary measurement of their potential impact. These decision rules can be schematically classified into three main types: (1) quantitative and/or qualitative criteria, (2) economic thresholds, and (3) a combination of both. In turn, these rules can generate two types of response. On the one hand, they can determine whether some regulatory projects should be exempted from the requirement to prepare an RIA and, on the other hand, for those regulatory projects that should be subject to an RIA, they can differentiate between different levels and scopes of analysis (i.e., types of assessment or RIA).

Proportionality Systems from International Perspective

In practice, proportionality systems vary widely among countries. The experiences of seven countries with a long tradition in the use of RIA and a mature better regulation policy with at least twenty years of implementation, are briefly described below for illustrative purposes.

Australia. In Australia, all proposals that are submitted to Cabinet are required to undertake a Regulation Impact Statement (RIS), as are all decisions by the government and its agencies that have potential impacts – positive or negative – on businesses, community organizations or individuals, unless the proposed change is “minor” or “machinery”. According to the Regulatory Impact Analysis Guidance (2020), the RIA is mandatory for any regulatory proposal before Cabinet, since it needs to be informed of the regulatory impact of any decision to be taken, the RIA must be submitted even if it is considered that there will be no impact on businesses, community organizations or individuals. For this purpose, the Australian government has a preliminary RIA to determine whether the draft regulation has “significant” impacts and should therefore be the subject of an extensive RIA (with more questions and detail and therefore requiring more analysis), or even whether it will require a detailed and monetized measurement of the costs involved[3].

Canada. In Canada, all subordinate regulations must perform an RIA. A triage system is used to determine the type of RIA (low, medium, or high impact) to which the regulatory proposal must be submitted. Based on a triage statement, which uses quantitative (threshold) and qualitative indicators, the regulatory analysis to be carried out are the following types:

- Low-impact analysis: when the present value of the costs is less than US$10 million over a 10-year period or less than US$1 million per year.

- Medium-impact analysis: when the present value of the costs fluctuates between $10 million and $100 million over a 10-year period or between $1 million and $10 million per year; and

- High-impact analysis: when the present value of the costs is greater than $100 million over a 10-year period or greater than $10 million per year[4].

In the case that the regulatory proposal presents no regulatory costs or impacts, then the Canadian system provides for the preparation of a low impact RIA but does not exempt it from submission.

South Korea. In South Korea the requirements to conduct an RIA apply to both draft legislation and subordinate or secondary regulations. The guidelines set out the criteria for determining whether a regulatory project could have a “significant” or “non-significant” impact. In the case of “non-significant” draft regulations, regulators must submit a qualitative analysis in which certain elements of the assessment may be omitted if they are judged as unnecessary. For a regulatory project to be considered “significant”, it must meet one or more of the following criteria (OECD, 2000).

- Potential annual impact exceeds 10 billion won.

- Has an impact affecting more than 1 million people

- Clearly limits competition in the market

- Represents a clear deviation from international standards

In this case, the project promoters must carry out a complete and detailed analysis with quantitative measurement of costs and benefits.

United States of America. The United States has a quantitative threshold for determining whether the (subordinate) regulation should perform an extensive RIA. Thus, under Executive Order 12866, the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) is responsible for determining which regulatory actions are “economically significant” or important in order to be subject to interagency review through an extensive RIA. Significant regulatory actions (or significant regulatory projects) are those that[5]:

- Have an annual effect on the economy of $100 million or more.

- Adversely affect in a material way the economy, a sector of the economy, productivity, competition, jobs, the environment, public health or safety, or State, local, or tribal governments or communities.

- Create a serious inconsistency or otherwise interfere with an action taken or planned by another agency.

- Materially alter the budgetary impact of entitlements, grants, user fees, or loan programs or the rights and obligations of recipients thereof; or

- Raise novel legal or policy issues arising out of legal mandates, the President’s priorities, or the principles set forth in this Executive order.

Although it is not explicit, it is understood that regulatory proposals that do not represent a significant economic impact are exempt from submitting the RIA.

United Kingdom. In the UK, as in the US, a monetary threshold is used to determine whether the RIA requires mandatory independent review and the level of analysis required. This threshold is given by the Equivalent Annual Net Direct Cost to Business (EANDCB) of +/-5 million Pounds Sterling (±£5m EANDCB). Where the quantitative assessment suggests that a regulatory proposal is below the threshold (-£5m EANDCB), a less detailed RIA, but proportionate to the expected impacts, may be chosen and its independent review is optional; otherwise, for a regulatory proposal above the threshold (+£5m EANDCB), a more detailed RIA, including quantification of impacts[6], is required and independent review is mandatory; finally, if the quantitative assessment falls within the specified range (±£5m EANDCB) the level of analysis should be proportionate, but a self-assessment by the agency is sufficient without the need for independent review.

It should be noted that the Regulatory Policy Committee (RPC), the body in charge of conducting independent reviews of RIAs, has a guide containing the proportionality criteria it uses in its reviews and the expected level of analysis, which distinguishes between low, medium and high impact assessments; however, it is only applicable to regulatory proposals that are submitted for independent review and serves to guide those in charge of conducting the analysis on the expected level of detail and depth of the analysis.

Switzerland. Switzerland has two types of RIAs, a simple or basic RIA and an in-depth RIA. The former is mandatory for all federal laws and government ordinances, while the latter is required for only selected legislative proposals that potentially have significant economic effects. The simple or basic RIA is known as a “quick check,” and is a two-page form that “is intended to provide at an early stage a first preliminary estimate of the major effects of regulatory projects”[7]. In the in-depth RIA, the analysis is more detailed, and the estimated impacts are quantified. To determine which type of RIA is applicable or if an RIA is not required, a preliminary three-step review is conducted, analyzing: 1) the scope of application of the RIA, 2) the economic and regulatory importance, and 3) other criteria (such as regulatory discretion). The criteria used to determine the economic and regulatory importance include the main groups affected, the number of companies involved, the degree of international openness, effects on competition, among others[8].

Mexico. In Mexico, the proportionality rule for identifying regulatory projects that require the submission of an RIA consists of determining whether the draft regulation to be submitted imposes compliance costs for private parties[9]. If the regulatory project does not impose compliance costs on private actors, the regulator may request an exemption of RIA[10]. In a second stage, the Mexican government uses another mechanism to measure the potential impact of regulation and thus keep applying the principle of proportionality to those projects that do involve compliance costs: the regulatory impact calculator. This consists of answering a short questionnaire with multiple choice answers, from which the level of impact of the regulation is determined. This calculator includes questions about the characteristics of the regulation, such as the sector to which it belongs, the economic processes involved, the number of consumers and economic units regulated, and the type of legal provision. Depending on the score provided by the calculator and according to a previously established threshold (a threshold that is internal to the system and is not publicly known), the type of RIA to be prepared by the regulator is determined. A score below this threshold will lead to a moderate or simplified impact RIA and a score above it will lead to a high impact or extensive RIA Thus, the Mexican system has a two-step proportionality rule; the first refers to the compliance cost criterion whose objective is to discern between those regulatory projects that do or do not require an RIA; while the second refers to the regulatory impact calculator whose aim is to differentiate the depth of the RIA analysis to be performed.

As can be seen, the proportionality systems have different rules, some more complex than others. In some countries it is identified that RIA is mandatory and there are few cases in which there is the possibility of exempting its presentation, even if there are no costs for companies or individuals. Only in Mexico and South Korea are exemptions explicitly provided for. The following section presents the case of Mexico in more detail.

Exemption from the Application of the RIA: The Mexican Case

Since its beginnings in 2000, Mexico’s regulatory review system has been based on various legal, technological, and procedural figures, which have given life to the regulatory improvement process: an administrative procedure whereby the regulatory oversight body[11] analyzes and reviews regulatory proposals from governmental agencies[12], under certain evaluation criteria, in order to ensure that the regulation “outweighs the costs and provides the maximum benefit to society”.[13]

In Mexico, the regulatory reform process is applied extensively and broadly in regulations enacted by the federal government and, to a lesser extent, by local governments[14]. Although there are certain areas exempt from the application of the regulatory improvement policy (also known as better regulation policy in English) —specifically, “tax matters[15], responsibilities of public servants, Public Prosecutor’s Office in the exercise of constitutional functions, and acts, procedures or resolutions of the Ministry of National Defense and the Ministry of the Navy (GLRI, Article 1) — these are minimal. On the other hand, there are no restrictions as to the type of regulations or general administrative acts subject to the regulatory reform process. Consequently, practically all types of regulations produced by the (federal) executive branch are subject to regulatory review.

In the Mexican system, the main tool for reviewing regulatory proposals within the regulatory improvement process is the regulatory impact analysis (RIA) (before named regulatory impact statement —RIS). In addition to this tool, the process considers other elements of similar relevance for the functioning of the system as a whole. Among these elements are deadlines and types of response that the regulatory improvement authority (CONAMER) must respond to revisions it carries out, transparency rules of the regulatory improvement process, the public consultation rules of the process, and the cooperation and collaboration mechanisms between public institutions that seek to generate regulatory coherence during the process of drafting regulations[16].

In order to implement the RIA, the Mexican model has had as a key element of decision making, the concept of compliance costs for private parties. It should be noted that the OECD (2014) has pointed out that the assessment of compliance costs is an important element of the RIA (p. 7). However, in the Mexican case, despite being a relevant concept for the functioning of the system, its definition has not been established in Law. Neither the Federal Law of Administrative Procedure (LFPA, which supported the regulatory reform policy in Mexico from 2000 to 2018) nor the General Law of Regulatory Improvement (GLRI, the new law that regulates the matter, published in May 2018) provides a concrete definition of the concept of compliance costs for private parties; however, the term is used in at least in four provisions of the new general law[17].

To cover this omission, at that time, CONAMER’s predecessor body (COFEMER) developed the definition of compliance costs in a secondary regulation — the Regulatory Impact Assessment Manual. Although the Manual was drafted in the early 2000s, it was formally published in the Official Gazette of the Federation (Diario Oficial de la Federación) until mid-2010.[18]

The definition of compliance costs and the legal provisions related to this definition are the cornerstone of the Mexican regulatory review system. The confidence that society, regulators and the regulated may have in the system derives from the correct application of this rule. Therefore, we have decided to address in this study the first step of the proportionality rule of the Mexican regulatory review system, the compliance cost rule.

Definition of Compliance Costs

Broadly speaking, the concept of compliance costs refers to those “costs that are incurred by businesses or other parties at whom regulation may be targeted in undertaking actions necessary to comply with the regulatory requirements, as well as the costs to government of regulatory administration and enforcement” (OECD, 2014, p. 12). For the OECD (2014), “compliance costs can be further divided into administrative burdens, substantive compliance costs and administration and enforcement costs” (p. 12).[19]

In the case of Mexico, emphasis is placed on the identification of compliance costs for individuals (companies and citizens), which includes administrative burdens and substantive compliance costs; however, the identification of the costs of administration and enforcement of the regulation is omitted, assuming them as costs of government management.

Thus, in the Mexican system, according to the RIA handbook[20], compliance costs for private parties are incurred when regulatory proposals seek one or more of the following actions:

- Create new obligations for individuals.

- Tighten existing obligations.

- Reduce or restrict rights or benefits for individuals.

- Create or modify formalities, except when the modification simplifies and facilitates the compliance of the individual.

- Establish definitions, classifications, characterizations, or any other terms of reference, which jointly, with another provision in force or with a future legal provision, affect or may affect the rights, obligations, benefits, or procedures of individuals.

These actions are part of the regulatory activity carried out by regulatory bodies and government agencies; however, they are supervised by CONAMER in order to verify that they are rational in economic, technical and legal terms. On the other hand, when these regulatory actions are analyzed in the light of a specific regulation, they allow the precise identification of the costs that this regulation imposes on citizens, since, in the absence of the regulation, the citizen would not be obliged to incur that cost or would not be limited to carry out a certain activity.

In addition to the above, this concept has been used directly as a decision rule to operationalize the principle of proportionality. The rule essentially consists of taking the concept of compliance costs, which is integrated by the five key criteria mentioned above, to determine when a regulatory proposal to be submitted to the process of regulatory improvement must be accompanied by an RIA and when it should not. In this sense, the Mexican system has configured a proportionality rule under the concept of compliance costs.

When —according to the regulator— the project does NOT have compliance costs, the Mexican system contemplates the legal figure of RIA exemption, in which regulators only submit to CONAMER a three-question form to inform about the public problem to be solved, the objectives of the regulation under review and a statement of no costs. Regarding the statement of no costs sending by regulators, CONAMER has the power and obligation to verify that the preliminary project does not present compliance costs for the individuals and, in case of presenting them, it is obliged to evidence the costs, reject the exemption and request the presentation of an RIA.

Originally, the rule was established in Article 69-H of the Federal Administrative Procedure Act, which stated that “regulatory proposals that do not imply compliance costs for private parties should be exempted from the obligation to prepare the RIA”. Currently, the GLFI retakes this decision and establishes in its article 71, the following:

“[…]

When a Regulated Entity considers that the Regulatory Proposal does not imply compliance costs for individuals, it will consult with the corresponding Regulatory Improvement Authority, which will resolve within a term that may not exceed five days, in accordance with the criteria for the determination of such costs established for such purpose in the Regulatory Impact Analysis Operating Manual issued by each Regulatory Improvement Authority. In this case, the obligation to prepare the Regulatory Impact Analysis shall be exempted”

[…]” (Article 71, GLFI). Emphasis added.

Given the above, the link between the concept of compliance costs and the proportionality rule for exempting an RIA is clear. This rule is generally applicable and does not make any distinction between types of proposed projects, sectors, or governmental organizations.

Using the concept of compliance costs for the implementation or not of the RIA is a reasonable scheme to put into practice the principle of proportionality, since it looks to generate administrative efficiency. That is, it seeks to allocate efficiently government resources, in order to focus them on the study of those regulatory projects that imply greater risks or a greater impact on society and that may modify the social or economic dynamics of the country. In defense of the joint use of the proportionality rule and the definition of compliance costs, it can be pointed out that they make possible to identify, quantify and monetize, in practice, the regulatory costs within the regulatory proposals, and also thus facilitating the development of an RIA. At the same time, the principle of proportionality under the compliance cost rule favors the exercise of identifying the regulatory proposals that should be analyzed in depth through an RIA, from those that should not. In this sense, this text seeks to make a deeper analysis of the effectiveness of the Mexican proportionality rule in its first stage.

Proportionality Rule Statistics

According to CONAMER data[21], from 2000 to 2020, 22,604 regulatory proposals were reviewed under the concept of compliance costs, equivalent to 93.7 percent of all regulatory projects (24,128) that were reviewed at CONAMER during that period[22]. Of that subtotal (22,604), 15,721 regulatory projects were classified as haven’t compliance costs, while 6,883 proposals were classified as having compliance costs. This means that 30.5 percent of the regulatory proposals examined under the concept of compliance costs had to submit an RIA, while 69.5 percent were exempted from the application of the analysis (see Graph 1).

Graph 1. Historical Series of Regulatory Proposals Received with and Without Compliance Costs

Source: Own elaboration with data from the Progress Report on the implementation of the National Strategy for Regulatory Improvement of CONAMER, 2018-2019.[23]

The available information shows that regulatory projects with compliance costs increase every three years. For example, from the period 2001 to 2003, 2003 is the year with the highest number of regulatory proposals with compliance costs; from the period 2004-2006, in 2006 there is an increase in the number of this type of preliminary drafts; the same occurs for the periods 2007-2009, 2010-2012 and 2013-2015; however, the trend is broken in the period 2016-2018. This pattern of behavior coincides with the changes of legislature in the Chamber of Deputies and could, therefore, be related to the receipt of secondary regulation derived from the issuance of primary regulation due to the closing of legislative cycles. At the same time, it could be related to the closing of federal administrations (see years 2000, 2006, 2012 and 2018).

There is also a higher degree of variability in the submission of regulatory proposals with compliance costs compared to those without compliance costs[24]. If it is true that the latter have a more stable behavior, it is important to note a new observable tendency between 2017 and 2020 consisting of a steady increase in the proportion of regulatory proposals without compliance costs, passing from 72 percent to 88 percent of all regulatory proposals reviewed under the compliance cost rule in that period. This means that in 2020 almost 9 out of every 10 proposals reviewed by CONAMER under this rule were reviewed through the RIA exemption provision. The change is significant if it is considered that in the 2010-2016 period, on average, 7 out of 10 regulatory projects were reviewed via this provision.

Eleven federal agencies were responsible for 85 percent of the regulatory proposals with compliance costs: The Ministry of Economy (SE), the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit (SHCP), the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT), the Ministry of Agriculture (SAGARPA/SADER), the Ministry of Energy (SENER), the Ministry of the Interior (SEGOB), the Ministry of Health (SSA), the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS), the Ministry of Education (SEP), the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), and the Ministry of Communications and Transportation (SCT).

Effectiveness of the Mexican Proportionality System

In light of the information presented and considering the high percentage of regulatory proposals that do not generate compliance costs (69.5 percent in the period 2010-2020)[25], one may wonder about the effectiveness of the proportionality system in discriminating regulatory projects with relevant impacts from those that do not. From this, two questions arise: (1) Has the concept of compliance costs for private parties been correctly applied in the analysis of the regulatory proposals? and (2) Is the concept of compliance costs for individuals, as currently defined, sufficient to effectively capture the potential impact of regulations and therefore serve as a proportionality rule to exempt RIA submission?

Design and Method of the Study

To answer these questions, we set out to identify the RIA exemptions requested from CONAMER during the period 2010-2020[26]. From the information obtained, it was identified that during the period from January 2010 to November 2020, 8,042 RIA exemption requests were submitted to CONAMER. Of this total, 85 percent of the exemptions in the last ten years are concentrated in 30 agencies[27], of which the eleven agencies listed above have the highest number of preliminary projects with compliance costs sent to CONAMER.

In order to analyze these 8,042 regulatory proposals with an RIA exemption request, a random sample of 69 regulatory proposals was obtained[28], with 90 percent confidence[29]. Of these 69 regulatory proposals, 6 cases (8.7 percent) could not be analyzed in light of the research questions that were initially proposed, because in three of the cases the regulatory proposals file did not contain the CONAMER resolution[30]; in two cases the regulatory projects were cancelled prior to CONAMER’s resolution; and in one case CONAMER’s resolution stated that the regulatory project did not comply with the rules for regulatory improvement in force at the time of the review.

Therefore, the sample effectively analyzed with the research questions was 63 regulatory projects, maintaining the confidence level of 90 percent. Of the 63 regulatory proposals analyzed, 29 (46 percent) were identified as administrative regulations, 20 (32 percent) as social regulations and 14 (22 percent) as economic regulations[31][32]. These 63 regulatory proposals were submitted to a review by three reviewers, with the purpose of identifying the following:

- Track CONAMER’s response times to RIA exemption requests.

- Identify comments received.

- Identify whether CONAMER’s resolution is consistent with the definition of the concept of compliance costs.

- Identify whether the compliance cost criteria are sufficient to assess the impact of the regulations.

The analysis of these proposals was carried out according to the following method: one reviewer reviewed all the regulatory proposals in the sample, another reviewer conducted a second review of the regulatory proposals where the first reviewer differed with CONAMER’s resolution. The third reviewer randomly reviewed a portion (22 percent) of all the regulatory proposals in the sample.

The first revision was carried out by one of the authors of this text, who has eight years of experience in the exercise of the regulatory review and in the application of CONAMER’s criteria in different economic sectors and five years of experience in the study of good regulatory practices. The review method consisted of analyzing the documents in the electronic file of each of the pre-projects in the sample, namely: 1) the text of the regulatory proposal, 2) the AIR exemption request form, 3) the response document issued by CONAMER to the regulator, and 4) if applicable, the comments sent by individuals. The purpose of this first review was to verify that the regulatory project had no costs, or otherwise, to identify possible costs in light of the definition of compliance costs. Likewise, it was verified if CONAMER made any indication of possible costs in its response.

This first revision resulted in several regulatory proposals that did not coincide with CONAMER’s response. Therefore, the second reviewer was given the task of examining, once again, only of those proposals that did not coincide with the authority’s response. The second reviewer is an external reviewer with more than five years of experience in the analysis of regulations. The analyses of the first reviewer and the second reviewer had few discrepancies, which were discussed and solved internally and allowed adjusting the database of “non-agreement with CONAMER’s resolutions”. The third reviewer was another of the authors of this text, who has more than ten years of experience in the preparation of RIAs and in the study and implementation of good regulatory practices. Based on the agreed database between the first and second reviewers, the third reviewer randomly reviewed one fifth of all the regulatory projects; again, there were minimal discrepancies in the review. Once all possible internal differences that arose in the analysis had been discussed, a single database was created, and the analysis and discussion of the data began.

Since this is a case study that seeks to evaluate the application of the Mexican proportionality rule under the concept of compliance costs, the review mechanism used was the opinion of experts or people with extensive knowledge and experience in the application of the concept of compliance costs, not only in one economic sector but with experience in the application of the rule in various economic sectors. Likewise, the expert triangulation technique was used, which made it possible to have a common and consensual base of expert opinion.

Results of the Study

The main results of the review are described below.

- Authority Response Times.

The average response time in which CONAMER resolved RIA exemptions, from 2010 to 2020, was 4 business days (equivalent to 6 calendar days). As can be seen in the following graph, the average annual response time was substantially modified as of 2011, one year after several modifications were introduced to the regulatory improvement system through the publication of the Agreement on deadlines for the resolution of preliminary projects and the Regulatory Impact Assessment Manual[33].

In this agreement, CONAMER established a maximum resolution period for RIA exemptions of 5 business days (equivalent to 7 calendar days). This term modified the maximum term of 90 calendar days, which was regularly used based on Article 17 of the FAPA. Thus, in 2010, the average term for the resolution of exemptions was 14.3 business days and in the period between 2011 and 2020, the term was reduced to an average of 3.5 business days (equivalent to 5 calendar days).

Graph 2. RIA Exemption Resolution Times, Annual Average in Working Days, CONAMER 2010-2020

Source: Own elaboration with data from SIMIR, CONAMER.

On the other hand, response times differed according to the type of regulation. As such, administrative regulation drafts were resolved in 3 working days on average, economic regulation drafts were resolved in 3.6 working days, while social regulation drafts were resolved in 6 working days. Likewise, there were variations in CONAMER’s resolution times according to the different agencies, as shown in the following table.

Table 1. Average Response Times for RIA Exemptions by Agency

| Time in working days | Agencies selected for the sample |

| 2 WD | IMSS, SCT, SEDESOL (BIENESTAR) |

| 3 WD | CRE, SRE, CNH, CONAPRED, SEDATU, SEP, SE, CIAD, INAPESCA |

| 4 WD | SEGOB, STPS, SAGARPA, CONACYT, ISSSTE, SHCP, SSA, SEMARNAT |

| 5 WD | PROFECO[34] |

| 8 WD | SENER[35] |

Source: Own elaboration with data from SIMIR, CONAMER.

- Participation in Public Consultation and Regulator- Oversight Body Interactions

Regarding public consultation, it is observed that during the period of analysis in only 3 of the 63 regulatory proposals (4.7 percent) did individuals submit comments. In this sense, the participation of individuals in regulatory improvement processes related to preliminary drafts with RIA exemption request tends to be almost null.

On the other hand, in the RIA exemptions analyzed, it is observed that during the regulatory improvement process it is common to have only one interaction between the regulator and CONAMER, that is, the regulator sends the exemption request and CONAMER tends to respond favorably without requesting more information, rejecting the exemption, or making any other requirement. It is a clear fast track process.

- Regarding the Resolution of Regulatory Proposals

From the review conducted, we identified that in all cases (63 regulatory proposals, 100 percent of the cases) the authority accepted the RIA exemption requested by the regulators. Of these resolutions, our analysis coincided with CONAMER’s resolution in 50 cases (79.4 percent), i.e., the absence of compliance costs for private parties was confirmed, and therefore the RIA exemption was accurately granted. In 4 cases (6.3 percent) it was not possible to determine whether the regulatory proposals of the sample contained compliance costs, since there is not enough information in the file to determine it. And in 9 cases (14.3 percent) our analysis did NOT confirm the absence of compliance costs, that is, it was identified that the preliminary projects did have costs and, despite this, CONAMER exempted the RIA, contravening the proportionality rule under the concept of compliance costs.

Of the 9 drafts where there was NO agreement with CONAMER’s resolution, in all cases the concept of compliance costs in force is sufficient[36] to resolve and evaluate the possible impacts; however, the criteria of this concept were not applied correctly. In each of these 9 regulatory projects, one to three compliance costs were identified (see Table 2).

Tabla 2. Tipos de Costos Identificados en Proyectos que Obtuvieron Exención de AIR

| Identified cost | No. of projects in which costs have been identified |

| Costs for creating obligations | 4 |

| Costs for the establishment of definitions and/or classifications that together with other legal provisions may affect the rights, obligations, benefits or procedures of individuals. | 4

|

| Costs for the creation of paperwork/formalities | 2 |

| Costs for tightening existing obligations | 2 |

| Costs due to restriction of rights | 1 |

Source: Own elaboration with data from SIMIR, CONAMER.

On the other hand, of the 50 regulatory projects that did coincide with the RIA exemption resolution granted by CONAMER, it was identified that in 41 cases (82 percent of the 50 cases) the criteria of the compliance cost concept were correctly applied and are sufficient to evaluate the potential impacts of the regulation; However, in the remaining 9 cases (18 percent), the criteria of the compliance cost concept were correctly applied but they are not sufficient to assess the potential impacts of the regulation, i.e., they do not capture all the potential relevant costs of the regulation, especially those costs that could be categorized as indirect costs of the regulation[37].

The costs that we identified in the preliminary regulatory projects, and for which we consider that the compliance cost criteria of the Mexican system are not sufficient to analyze the costs of the regulations, are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Costs Identified as Being Outside the Scope of the Compliance Cost Criteria in the Mexican Regulatory Review System

| Type of cost | Relation | Cost level | Impacts | Example of a regulatory proposals in which the following were identified |

| Costs for establishing tariffs through acts of authority towards concessionaires | Direct | Meso | Establishment of tariff systems for concessionaires that will affect the costs of provision of and access to public goods and services by private parties. | Maximum airport tariffs applicable to airports |

| Costs of generating uncertainty for private parties through regulator discretionality | Indirect | Micro | These costs result in administrative burdens that are hidden in general administrative acts in which the authority establishes certain rules that broaden the discretionary power of street-level bureaucrats through confusing, non-transparent and unclear rules. | Agreement on non-working days for the purposes of administrative acts and procedures under the competence of SEDATU, to prevent the spread and transmission of the covid-19 virus. |

| Direct costs for the establishment of regulatory actions as a technical recommendation through technical studies | Direct | Meso | Technical studies may include suggested rules or decision thresholds, such as limits for government action, which may impact the rights and obligations of the target populations of the studies in question. | Agreement disclosing the results of the technical studies of national groundwater of the Amazcala Valley aquifer, Querétaro. |

| Costs for modification of the market structure through new regulatory attributions to regulatory agencies | Indirectos | Meso | They are new rules of a market that are not issued through a specific regulation for that purpose (modification of the market structure). | Agreement issuing the policy for reliability, safety, continuity and quality in the national electric power system[38] |

Source: Own elaboration

Note: Meso-level costs are understood as the direct or indirect costs of regulation in social structures such as economic markets, population groups or geographic regions.

Discussion

In this research we have identified that, for the Mexican case, the effectiveness of this rule in the 2010-2020 period ranges from 65 to 71.4 percent[39], which means that maximum in 7 out of 10 regulatory proposals the proportionality rule is adequately applied and fully captures potential impacts of the regulations. In other words, the rule of proportionality for the concept of compliance costs allows to adequately discriminate regulatory proposals that do not generate compliance costs for individuals and, therefore, do not require an exhaustive use of technical resources to deepen the analysis of the impacts they could generate.

Nevertheless, there are two major problems that undermine the effectiveness of the proportionality rule. On the one hand, there are inconsistencies in the application of the criteria of the concept of compliance costs and, on the other hand, the rule has limitations to assess the regulatory proposals that could generate significant impacts (direct or indirect) on specific economic sectors, population groups or geographic areas.

Graph 3. Analysis of the Effectiveness of the Proportionality Rule by Compliance Costs

Source: Own elaboration

On the Application of Compliance Cost Criteria

Although the regulatory body may misunderstand, misinterpret, and misapply the criteria of the concept of compliance costs, CONAMER, as the national regulatory improvement authority, is empowered to correct the regulator’s assessment in the application of these criteria. The formal mechanism that CONAMER has to exercise this power is the issuance of a resolution in which it rejects or accepts the regulator’s request for exemption from RIA for no costs.

The adequate application of this rule is the turning point to ensure that regulations are analyzed correctly and that the regulatory reform policy generates a quality regulatory framework, since, as established by the General Law for Regulatory Improvement (GLFI) itself, a proposal that generates costs must be analyzed in light of a regulatory impact assessment, through which the regulatory reform authority must guarantee that the regulatory proposals generate benefits that exceed the costs and the maximum benefit for society, as well as coherence among public policies (GLFI, articles 66-79).

In this sense, if CONAMER does not correctly apply the compliance cost criteria and accepts RIA exemption requests when the regulatory proposal does generate costs, it would be committing type II error (false null hypothesis, but it is accepted), so the regulatory proposal will not be analyzed under the standards established by the law (which are aligned with international standards[40]) Therefore, neither the maximum social benefit nor the quality of the regulations nor the coherence between policies could be guaranteed. This becomes more worrisome if we take into account the growing trend of regulatory proposals without compliance costs with respect to the total number of regulatory proposals received by the regulatory improvement authority.

Furthermore, a CONAMER resolution that clearly violates or contravenes the criteria of the compliance cost concept jeopardizes the reputation and credibility of the authority and of the regulatory reform system as a whole, which reduces the trust of citizens in the governmental processes of elaboration, discussion, and review of regulations.

Reputation is based on the historical performance of the organization or a system. (Lange et al., 2011, p. 154) and is crucial to achieving stable and positive solutions (Stern y Holder, 1999, p. 38). However, this can change abruptly (p. 154); one or two partial decisions are enough to seriously undermine a good regulatory reputation (p. 38). The maintenance of the reputation of the regulatory improvement system and its institutions (rules and organizations) has an influence on stakeholders’ perception of whether the resolutions are good and appropriate and on the predictability of outcomes and behavior (Lange et al., 2011, p. 155) of CONAMER.

On the Limitation of the Rule to Capture Compliance Costs

In this problem we identified that the Mexican model focuses on capturing the direct costs that regulations impose on individuals (costs at the micro level) but fails to track and capture negative impacts (costs) at the meso and macro levels[41].

Costs at the meso level, for example, impacts on the structure and design of the market, or impacts that generate inconsistencies in the legal framework of an economic sector, may in the medium and long term generate direct and indirect costs to individuals. This is where some recent public debates on regulatory projects are framed, which, although they do not imply compliance costs for individuals (micro level), could have a direct impact on economic sectors, population groups or specific geographic areas, and an indirect impact on individuals or companies.

For example, on January 17, 2019, the Ministry of Energy (SENER) sent to CONAMER the draft Decree creating the Logistics Center for the Distribution and Transportation of Petroleum Products[42]. The Center’s objective is to “establish, implement and, where appropriate, execute the strategies and actions to promote the performance of the activities of distribution, transportation and storage of petroleum products and other related services”. The decree proposal was sent to CONAMER through an RIA exemption request. The same day that SENER sent the regulatory proposal, CONAMER exempted SENER from submitting an RIA since it considered the exemption to be appropriate in terms of the concept of compliance costs for individuals. Nevertheless, the President of the competition authority (COFECE) attracted public attention by criticizing the fact that the regulatory proposal was exempted from submitting the RIA on the same day it was sent to CONAMER[43], without proper public consultation[44]. On the other hand, the L.P. Gas associations submitted comments to the draft and warned of regulatory impacts from the industry’s perspective:

“… this regulatory product contains profound legal implications that considerably affect the L.P. Gas activities that it is intended to regulate…” (B000190153)

“… The creation of this new regulatory instrument would result in over-regulation, … the existing authorities are sufficient to regulate the distribution and transportation of petroleum products” (B000190180)[45]

“… This would create a distortion in the current regulatory framework, since it creates regulatory duplication between the CRE and the Administrative Body (to be created), which would lead to incremental costs for the LPG industry and regulatory authorities.” (B000190196, B000190241)[46]

“… distorts the institutional regulatory and normative scheme designed with the energy reform, to the detriment of end users and permit holders, which represents implicit High Impact costs due to the repercussions on the entire institutional model of the Oil Sector, including L.P. Gas.” (B000190196, B000190241).

As can be seen, the business chambers do not warn of direct costs to companies in the short term (micro), but rather warn of risks due to uncertainty, duplication of regulation and possible over-regulation in the LP Gas industry, which could be reflected in direct and indirect costs at the meso level.

The problem of having a limited rule to capture all the possible negative impacts of a regulatory project, in its various levels of analysis, is related to the design of the regulatory review system, rather than to the authority’s decision to exempt from RIA a regulatory proposal. Failure to consider all the costs of regulation, however, may result in not guaranteeing -as mandated by law – “the maximum benefit for society”, neither that the regulation adopted is of higher quality[47], hence the importance for regulatory review systems to have clear, complete, and transparent rules and definitions of compliance costs.

In this sense, we consider that the criteria for the concept of compliance costs in Mexico are limited because they focus exclusively on the direct costs to individuals, whether companies or citizens, but fail to consider the negative impacts at the meso and macro levels, that is direct or indirect costs to economic sectors, geographic areas or social groups, indirect costs to individuals, or else direct or indirect costs reflected in macroeconomic indicators. International experience shows that several countries include in their proportionality rules criteria that attempt to address the impacts of regulation at the meso and macro levels.

Table 4. International Experience: Examples of Criteria that are Part of the Proportionality Rules and that Capture Costs at the Meso and Macro Level

| Country | Criterion capturing impacts at meso and macro levels | Level of negative impacts |

| South Korea | The regulatory proposals represent a clear deviation from international standards. | Macro |

| South Korea,

Switzerland

|

The regulatory proposals clearly limit competition in the market. | Meso |

| United States | The regulatory proposals adversely affect in a material way the economy, a sector of the economy, productivity, competition, jobs, the environment, public health or safety, or State, local, or tribal governments or communities.

|

Macro/Meso |

| United States | The regulatory proposals create a serious inconsistency or otherwise interfere with an action taken or planned by another agency. | Meso |

| United States | The regulatory proposals materially alter the budgetary impact of entitlements, grants, user fees, or loan programs or the rights and obligations of recipients thereof. | Meso |

Source: Prepared by the authors with information from the regulatory systems of the countries indicated.

The criteria used in the United States, for instance, are broad and allow for capturing the potential negative impacts of regulations from different levels, for example, whether a regulation ” creates serious inconsistencies or otherwise interferes with an action taken or planned by another agency” is a criterion that provides coherence to the regulatory framework of a nation, state or municipality, and allows identifying inconsistencies that could generate compliance costs to individuals in the medium and long term, even if at the time of issuing the regulation, no tangible and direct compliance costs to individuals were identified in the short term.

In this sense, preventing regulatory proposals with compliance costs at the meso or macro level from being exempted from presenting their corresponding RIA would allow for a complete mapping of the possible impacts of the regulation, not only in negative terms, but also in positive ones. This is important because the scope of regulations is not limited to citizens; they also impact economic and population sectors, specific regions and, in general, an entire country. Having clarity on the scope of regulatory impacts would make it possible to better approximate the net social benefit (positive or negative) of regulations.

Conclusions And Public Policy Recommendations

The regulatory review system in Mexico has been institutionalized since 2000. From the beginning, Mexico adopted a proportionality rule based on the concept of compliance costs. This rule has made it possible to efficiently manage the regulatory review system, since this mechanism has allowed discerning between regulatory projects that should be accompanied by an RIA and those that should not be accompanied by an RIA and should only be subject to a simple and minimal review, through an RIA exemption request.

In this text we have studied this proportionality rule based on the concept of compliance costs. The most relevant finding we have identified is that in 3 out of 10 regulatory proposals, the proportionality rule fails, either because the criteria are not adequately applied or because the criteria are limited to assess ex ante all possible negative impacts of the regulation. In order to improve the effectiveness of the proportionality rule in the Mexican case, we present below some recommendations that regulatory authorities could consider.

- Regulation of the concept of compliance costs in the Law or subordinate Law.

The lack of clarity and visibility of the criteria for the concept of compliance costs may lead to regulators and the regulatory improvement authority itself not applying them properly. As mentioned before, currently (April 2021) the criteria of the compliance cost concept are not defined in the GLFI and are only stated in the Regulatory Impact Analysis Manual (published in 2010). Because of the relevance of the concept, it is necessary that it be defined in the General Law or, at least, in its regulations.

- Further description of the compliance cost criteria.

The only reference available regarding compliance cost criteria is enunciative and is found in the RIA Manual. In other words, there is no guide for their application. In order for the regulated parties, regulators and the regulatory improvement authority to build the necessary technical capacities to apply the criteria correctly and consistently, it is necessary that these criteria be described in greater detail, either in the regulation of the Law, or in some other general administrative provision, such as a compliance cost guide or manual.

- Broadening the concept of compliance costs to capture negative impacts at all levels (micro, meso and macro).

To prevent regulatory proposals with relevant impacts, particularly at the meso and macro levels, from being exempted from preparing and submitting the RIA, it is important that the Mexican system evolves by including new criteria in the proportionality rule that capture the negative impacts generated by regulations at a meso and macro level, and even indirect impacts at the micro level. This would imply broadening the spectrum of the proportionality rule under the concept of compliance costs. These criteria should also be regulated and included in the General Law, its secondary regulation, or any other general legal provision.

- Training for regulators, regulated parties, and regulatory improvement authorities on the proportionality rule.

In order to homologate the understanding and application of the concept of compliance costs, including the possible adjustments to the proportionality rule suggested in this text, it is necessary for the Mexican regulatory reform authority to carry out extensive training for citizens, regulators and its own public servants. The homologated understanding of the criteria will allow to advance in their consistent application and in the construction of a better regulation culture.

- Establishing a minimum public consultation period for regulatory projects that are submitted “without compliance costs” and request exemption from the RIA.

It is important to ensure a minimum period of public consultation for regulatory proposals that are sent by regulators to CONAMER via a request for RIA exemption, so that individuals (companies and citizens) have the opportunity to submit comments to these proposals, allowing the regulatory improvement authority to verify from different perspectives that indeed the regulatory projects do not imply compliance costs or, if applicable, to reject the exemption and request a RIA. Currently, the General Law of Regulatory Improvement (art. 71) establishes a maximum term of five working days for the authority to resolve exemption requests, which implies that there is no minimum term for the consultation of this type of preliminary proposals; on the contrary, in practice, the response period has been reduced in the last three years up to 2.7 working days on average, and in some cases even granting the exemption on the same day it is requested by regulators. This clearly does not allow for an adequate and inclusive discussion of regulatory proposals, which limits the quality of regulations and, occasionally, may even harm market dynamics.

Finally, we would like to point out that this research is the first of its kind in Mexico, with it we seek to encourage a public and academic dialogue and debate that allows to improve the performance of regulatory policy based on available and observable information. We bet that this experience may be useful to other countries that are beginning the implementation of RIA —such as Brazil, Colombia, Peru and the Dominican Republic in Latin America—, integrating proportionality rules from the design stage of the regulatory review process that allow them to better manage the regulatory flow and anticipate possible failures of its rules and take corrective actions in a timely manner. We also hope that the discussion presented here may be useful to contribute to the issues on the international applied research agenda on good regulatory practices.

Limitations of the Study

It is important to recognize that the study faced limitations derived mainly from the information available. Thus, some of the regulatory proposals in the files analyzed referred to modifications of already existing regulations, which, being secondary regulations ten years old, it was not always possible to identify the regulation in force prior to the proposed modification. In addition, in some electronic files of regulations, neither the regulator nor the regulatory improvement authority presented discussions that would allow elucidating whether the possible costs identified in the proposals were additional to the existing ones or whether they were new costs. Although all the cases in which we found this situation were identified in the analysis sample, it is important to recognize that these situations limited the research findings, for instance by having to generate a range of effectiveness. In this sense, and in order to facilitate the development of applied research in regulatory reform, it will always be important that when regulators and regulatory reform authorities analyze regulatory projects that modify existing regulations, they can explicitly and clearly inform where those compliance costs that are found in the modification proposal under analysis derive from and why it is considered that it does not generate additional compliance costs.

On the other hand, although the database of AIR exemptions was provided by CONAMER through a request for information, it is important to note that the regulatory search system has some deficiencies. For example, although CONAMER’s regulatory review system is an open access system, it does not allow data to be obtained in aggregate. That is, the format in which they are found, and the few functionalities of its search engine do not allow obtaining databases that can be “freely used, reused and redistributed”[48]. In addition to that, for some regulatory files, there was an omission in the publication of CONAMER’s response to the regulatory project. Not having the complete dossier also limited the analysis of the data or implied greater research burdens.

Finally, it is important to highlight that the results presented here do not prejudge the general functioning of the AIR system in Mexico, since only a small part of it was analyzed. In this sense, these results allow us to better understand and provide evidence on the functioning of the first stage of the proportionality rule. We hope that future research can complement these analyses more broadly, through larger samples or even with alternative methodologies.

References

Australia, Government Guide to Regulatory Impact Analysis, second edition, 2020. Revisado el 11 de diciembre de 2020. Disponible en: https://www.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/australian-government-guide-to-regulatory-impact-analysis.pdf

Canadá, Triage Statement Form. Revisado el 11 de diciembre de 2020. Disponible en: https://www.canada.ca/en/government/system/laws/developing-improving-federal-regulations/requirements-developing-managing-reviewing-regulations/guidelines-tools/triage-statement-form.html

E.U.A, Executive Order 12866, September 30, 1993.

E.U.A., Regulations and the Rulemaking Process, OIRA. Revisado el 11 de diciembre de 2020. https://www.reginfo.gov/public/jsp/Utilities/faq.myjsp#oira

Lange, D., P. M. Lee & Y. Dai (2011), Organizational reputation: A review, Journal of Management, 37(1), 153-184.

Lee, J. (2017), Korean Practices and Challenging Issues in Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA). Revisado el 11 de diciembre de 2020. Disponible en: https://www.kdi.re.kr/kdi_eng/events/seminar_data_view.jsp?yyyy=2021&mseq=419&dseq=1716

México, Encuesta Nacional de Calidad Regulatoria e Impacto Gubernamental de Empresas 2016. Diseño Muestral. (ENCRIGE), INEGI. https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=702825093693

México, Ley Federal de Procedimiento Administrativo (LFPA), Título tercero A.

México, Ley General de Mejora Regulatoria (LGMR), Diario Oficial de la Federación, 18 de mayo de 2018.

OECD (2000), OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform: Regulatory Reform in Korea 2000, OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264181748-en.

OECD (2007), Glossary of statistical terms, Éditions OCDE, Paris. https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/download.asp

OECD (2008), Introductory Handbook for Undertaking Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA), Éditions OCDE, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/44789472.pdf

OECD (2009), Regulatory Impact Analysis: A Tool for Policy Coherence, OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform, Éditions OCDE, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264067110-en.

OECD (2012), Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264209022-en.

OECD (2014), OECD Regulatory Compliance Cost Assessment Guidance, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264209657-en

OECD (2020a), Regulatory Impact Assessment, OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7a9638cb-en.

OECD (2020b), A closer look at proportionality and threshold tests for RIA, Annex to the OECD Best Practice Principles on Regulatory Impact Assessment. http://www.oecd.org/regreform/Proportionality-and-threshhold-tests-RIA.pdf

Stern, J. and S. Holder (1999), Regulatory governance: criteria for assessing the performance of regulatory systems: An application to infrastructure industries in the developing countries of Asia, Utilities Policy, 1999, vol. 8, no 1, p. 33-50.

Suiza, Manuel Analyse d’impact de la réglementation, Département Fédéral de l’Économie de la Formation et de la Recherche, 2013. Disponible en https://www.seco.admin.ch/seco/fr/home/wirtschaftslage—wirtschaftspolitik/wirschaftspolitik/regulierung/regulierungsfolgenabschaetzung.html

United Kingdom, Better Regulation Framework: Interim guidance, March 2020. Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. Revisado el 11 diciembre de 2020. Disponible en: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/872342/better-regulation-guidance.pdf

Technical Annex

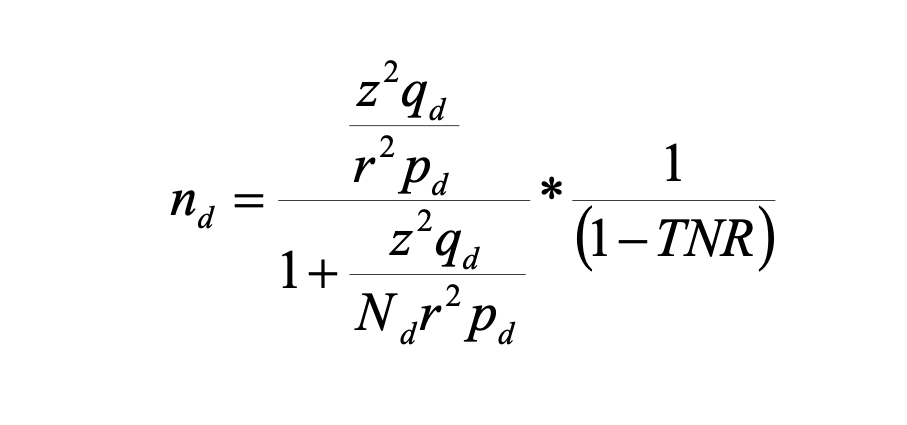

To analyze the proportionality rule, a database with 8,042 regulatory proposals that were sent to CONAMER via RIA’s exemption request between 2010 and 2020 was obtained from CONAMER’s records. This information was sorted by years and the sample size was obtained considering the following formula[49]:

Where:

nd = sample size

z = value in tables for a standard normal distribution.

Qd =1−Pd

r = relative level of error.

Pd = proportion of interest

Nd = total number of regulatory projects submitted as RIA exemption requests to CONAMER between 2010-2020

TNR = non-response rate.

A 90 percent confidence interval was taken, with a maximum expected relative error (r) of 15 percent by convention[50]. Also, based on statistical data obtained from the general historical record of regulatory proposals received by CONAMER between 2000 and 2020, it was identified that the probability of a regulatory proposal NOT having compliance costs is 69.5 percent (pd), while the probability of receiving a project WITH compliance costs is 30.5 percent (qd). A non-response rate (NRR) of zero was also considered, since these are not surveying and there are no previous records of information that could be considered as a simile of the non-response rate. The universe from which the sample was obtained was 8,042 regulatory proposals that CONAMER reported having received between 2010-2020 as RIA exemption requests.

Applying the formula, a sample size of 52.4 regulatory proposals was obtained; however, a total of 69 regulatory proposals were reviewed. To select the regulatory projects, the sample was distributed randomly and proportionally in each of the years analyzed (2010-2020), according to the annual proportion of preliminary projects with no costs received in CONAMER during that period.

Endnotes

- It is important to highlight that it was decided to carry out the study from 2010 to 2020, since in 2010 CONAMER modified, considerably, the rules of the regulatory review system regarding the types of RIA’s to be submitted when projects contain compliance costs. Therefore, it was considered that analyzing the compliance cost rule from 2010 onwards would allow a more accurate analysis of the regulatory behavior.

- In relation with TNR, once the sampling was carried out, it was identified that the non-response rate may be the equivalent to those regulatory proposals that could not be reviewed in light of the compliance cost proportionality rule because CONAMER’s response to RIA’s exemption request was not found in the electronic file, or the exemption request was withdrawn. In this sense, the non-response rate calculated, once the study was carried out, was determined to be 7.25 percent based on the five regulatory proposals for which the regulatory authority’s response could not be identified. This non-response rate could be used for future research related to the study of regulatory projects obtained from CONAMER’s regulatory review system.

| How to cite:

Perales-Fernández, F. & Velázquez-Roa, J. L. (2021) The regulatory review system in Mexico: the proportionality rule under the compliance cost concept. |

[1] Regulatory projects should be prepared at the same time or after the corresponding RIA is prepared.

[2] The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) recommends that, as part of the RIA governance system, RIA should be proportionate to the importance of regulation; see, for example, OECD (2012) and OECD (2020a).

[3] The Australian Government Guide to Regulatory Impact Analysis, second edition, 2020.

[4] For more information, consult the following link: https://www.canada.ca/en/government/system/laws/developing-improving-federal-regulations/requirements-developing-managing-reviewing-regulations/guidelines-tools/triage-statement-form.html

[5] https://www.reginfo.gov/public/jsp/Utilities/faq.myjsp#regrule.

[6] Better Regulation Framework, Interim Guidance, Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, March 2020.

[7] Analyse d’impact de la réglementation (RIA). https://www.seco.admin.ch/seco/fr/home/wirtschaftslage—wirtschaftspolitik/wirschaftspolitik/regulierung/regulierungsfolgenabschaetzung.html.

[8] Manuel, Analyse d’impact de la réglementation, Département Fédéral de l’Économie de la Formation et de la Recherche, 2013. Consultado en https://www.seco.admin.ch/seco/fr/home/wirtschaftslage–wirtschaftspolitik/wirschaftspolitik/reglierung/regulierungsfolgenabschataetzung.html el 07 de diciembre de 2020.

[9] The following section discusses the criteria used to determine whether a regulatory project imposes costs on private actor (individuals, organizations and companies).

[10] Article 71 of the General Law for Regulatory Improvement (GLRI).

[11] Also known as regulatory authority, metaregulator or regulator of regulators. In Mexico, at the federal and national level, the regulatory oversight body is the National Commission for Regulatory Improvement (CONAMER), which from 2000 to 2018 was called the Federal Commission for Regulatory Improvement (COFEMER).

[12] Among them, state secretariats, deconcentrated or decentralized regulatory bodies, etc.

[13] Article 69-E in force from April 2000 to May 2018 and Article 23 of the GLRI.

[14] That is states and municipalities that have a formal RIA implementation process. Since local governments operate autonomously from the federation and most of their regulatory reform systems are newly created, this paper focuses on the regulatory reform process at the federal level.

[15] In the case of contributions and accessories derived directly therefrom (Article 1, GLRI.)

[16] For example, the coordination between CONAMER and the Federal Economic Competition Commission (COFECE) for the review and opinion of draft regulatory projects with an impact on economic competition in the markets, as well as the coordination between CONAMER and the Undersecretariat of Foreign Trade for the review of draft projects with an impact on foreign trade, which may be susceptible to be notified to the World Trade Organization (WTO).

[17] Artículos 65, 71, 77, y 83.

[18] AGREEMENT establishing deadlines for the Federal Commission for Regulatory Improvement to resolve on preliminary projects and announcing the Regulatory Impact Assessment Manual. https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5153094&fecha=26/07/2010

[19] For a definition of these concepts see OECD (2014), pp. 12 and 13.

[20] Published in the Official Gazette on July 26, 2010.

[21] Information obtained from COFEMER/CONAMER Annual Report.

[22] Excludes 1,524 preliminary drafts referring to Rules of Operation of federal social programs, Requests for Opinions on International Treaties, and ex post evaluations of federal regulations, since these types of regulations are not evaluated under the concept of compliance costs.

[23] Available at the following web address: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/513247/Informe_anual_de_desempe_o_portal.pdf

[24] The coefficient of variation of the regulatory proposals with compliance costs is 48.85%, while the coefficient of variation of the regulatory proposals without compliance costs is 30.66%.

[25] As mentioned above, in recent years this percentage has grown to 88% in 2020.

[26] Due to the difficulty of the RIA system in Mexico to perform massive searches by type of request, the information was obtained through an information request via the national information platform administered by the National Institute of Access to Information (INAI).

[27] SE, SHCP, SEMARNAT, SAGARPA, SENER, SEGOB, SSA, IMSS, SEP, SFP, SEDESOL, CRE, STPS, SCT, SEDATU, SER, IMPI, ISSSTE, CENACE, CULTURA, PROFECO, SSPC, CONAFOR, CONACYT, SECTUR, CNH, CONAPRED, CEAV, CONDUSEF, DIF.

[28] The sample of 69 drafts includes 22 agencies: SE, SENER, SEGOB, SHCP, SAGARPA, SEMARNAT, IMSS, SEDESOL, SSA, STPS, CNH, CIAD, CRE, PROFECO, SCT, SEDATU, SRE, SEP, CONACYT, CONAPRED, ISSSTE and INAPESCA.

[29] For more information on the sample see the Technical Annex.

[30] This may be due, for example, to the inattention on the part of CONAMER’s public servants when uploading the corresponding resolution to the system or to other factors unknown to the authors of this document.

[31] The OECD distinguishes between: (1) Administrative regulations which are those that organize the attributions, functions and competencies of the governing bodies, and which also include legal provisions that regulate the paperwork and administrative formalities – so-called “red tape”- through which governments collect information and intervene in individual economic decisions (OECD, 2007, p. 22) and includes provisions that serve as a means of disseminating information of public interest on the functioning of the government to the population. (2) Social regulations are regulations that “protect public interests such as health, safety, the environment, and social cohesion” (OECD, 2007, p. 725), focuses on risk management and social programs or actions; y (3) Economic regulations refers to regulations that “intervene directly in market decisions such as pricing, competition, market entry, or exit” (OECD, 2007, p. 229).

[32] It is important to note that the classification of regulatory projects by administrative, social, and economic type was made considering the main provisions they contain and that characterize them, although in practice some regulatory projects could contain all types of provisions.

[33] DOF, July 26, 2010. https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5153094&fecha=26/07/2010

[34] The analyzed regulatory proposals of Profeco are from 2016 and 2017.

[35] SENER’s regulatory proposals are from 2011 and 2013. If the year 2010 were considered, the average term would be 11 working days.

[36] By sufficient we mean the ability of the criteria to capture all possible direct regulatory impacts and indirect costs of consideration.

[37] Indirect costs “also called “second round” costs, indirect costs are incidental to the main purpose of the regulations and often affect third parties. They are likely to arise as a result of behavioral changes prompted by the first-round impacts of the regulations” (OECD, 2014, p. 14).

[38] This regulatory proposal was not analyzed in the sample; however, it shows more clearly the cost that we are trying to illustrate.

[39] The 71.4 percent percentage is derived from the 63 cases analyzed minus the 9 cases in which the analysis is not correct and the 9 cases in which the criteria are not sufficient, leaving 45 cases (71.4%) in which the analysis is correct and the criteria are sufficient Nevertheless, if the 4 cases in which there was not enough information to be assessed are taken into account, the effectiveness percentage could drop to 65% if in these 4 cases the analysis was not correct or the criteria were not sufficient (see Graph 3).

[40] These standards aim to generate systematic analyses of regulatory proposals that allow the identification of the public problem to be solved, the justifications why the regulatory body considers the intervention of the State necessary, the possible alternatives considered and the justification of the intervention alternative chosen, as well as specific regulatory actions that are established in the regulatory instrument to be issued and that allow the quantification of the costs and benefits of the regulation. Among these main international standards, we can find the 2012 Recommendation of the Council of the OECD on Regulatory Policy and Governance, available at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/recommendation-of-the-council-on-regulatory-policy-and-governance_9789264209022-en

[41] Macro-level costs are, according to OECD (2014), those that impact “key macroeconomic variables, such as gross domestic product and employment, caused by regulatory requirements.” (p. 15).

[42] Electronic file of the regulatory proposal at CONAMER: http://www.cofemersimir.gob.mx/expedientes/22747

[43] Several journalistic notes of the tweet made by COFECE are identified: El Reforma, El Diario de Chihuahua; El norte.

[44] In her twitter account she said: “The government publishes in @CONAMER_MX (website) the project to create a new regulatory body on oil logistics issues. It is published there in order to have public consultation on the project. But they exempt it from RIA, so that it can pass “fast track”. https://twitter.com/JanaPalacios/status/1086107474292174848?s=20

[45] Comment available at: http://www.cofemersimir.gob.mx/expediente/22747/recibido/61067/B000190180

[46]Comments available at: http://www.cofemersimir.gob.mx/expediente/22747/recibido/61073/B000190196 y http://www.cofemersimir.gob.mx/expediente/22747/recibido/61097/B000190241

[47] See OECD (2014), p. 7.

[48] “Open data is data that can be freely used, reused and redistributed by anyone, and is subject, at most, to the requirement of attribution and sharing in the same way in which it appears.” Definition available at: https://opendatahandbook.org/guide/es/what-is-open-data/

[49] The formula for the sampling was obtained from the technical document of sample design of the National Survey of Regulatory Quality and Government Impact of Businesses 2016 (ENCRIGE) of INEGI.

[50] In the statistical projects of the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), it is common to observe the use of 15% as the maximum relative error expected to generate good quality estimates.